Health & Safety Management Plan

The Health and Safety at Work Act 2015 states that a person conducting a business or undertaking has a responsibility to

eliminate risks to health and safety, so far as is reasonably practicable; and if it is not reasonably practicable to eliminate risks to health and safety, to minimise those risks so far as is reasonably practicable.

To show that you have considered these aspects, you will need a general health and safety management plan. Ideally, it should include the following:

Identifying your hazards

Identifying your hazards

This involves walking through your institution and identifying possible hazards, such as places where people might slip, trip, or fall. Hazards could be hot or sharp objects, low ceilings, and other obvious things that may cause people harm. Then there are your “hidden hazards,” and these include but are not limited to:

- Asbestos

- Arsenic

- Batteries

- Biological Hazards

- Flammable liquids

- Lead

- Mercury

- Medicines and controlled drugs

- Moulds and fungi

- Nitrate film

- Poisons and pesticides

- Radiation

- Weapons, ammunitions, and explosives

Consider all the processes that you use and the people that utilise your institution when you are identifying possible hazards (staff, researchers, contractors – not just the visitors).

Catalogue your hazards

This will vary according to what type of hazard you are talking about, but it is important that anyone can come along, look at your hazard register, and then go and physically identify the hazard.

Each item should have a unique identification number, plus a description of the hazard (with a photo if possible). If the hazard is a chemical, record the volume, trade name, and the type of container.

Assessing the risks

Assessing the risks

There are a whole range of scenarios that can occur, from the institution burning down, or someone getting salmonella, to a person becoming unconscious after inhaling chemical fumes, or someone becoming allergic to mould. You are the ones that are more familiar with the possible hazards in your institution than anybody else, so this is your call. Here are some of things you may wish to consider:

Eliminate the risk where practical

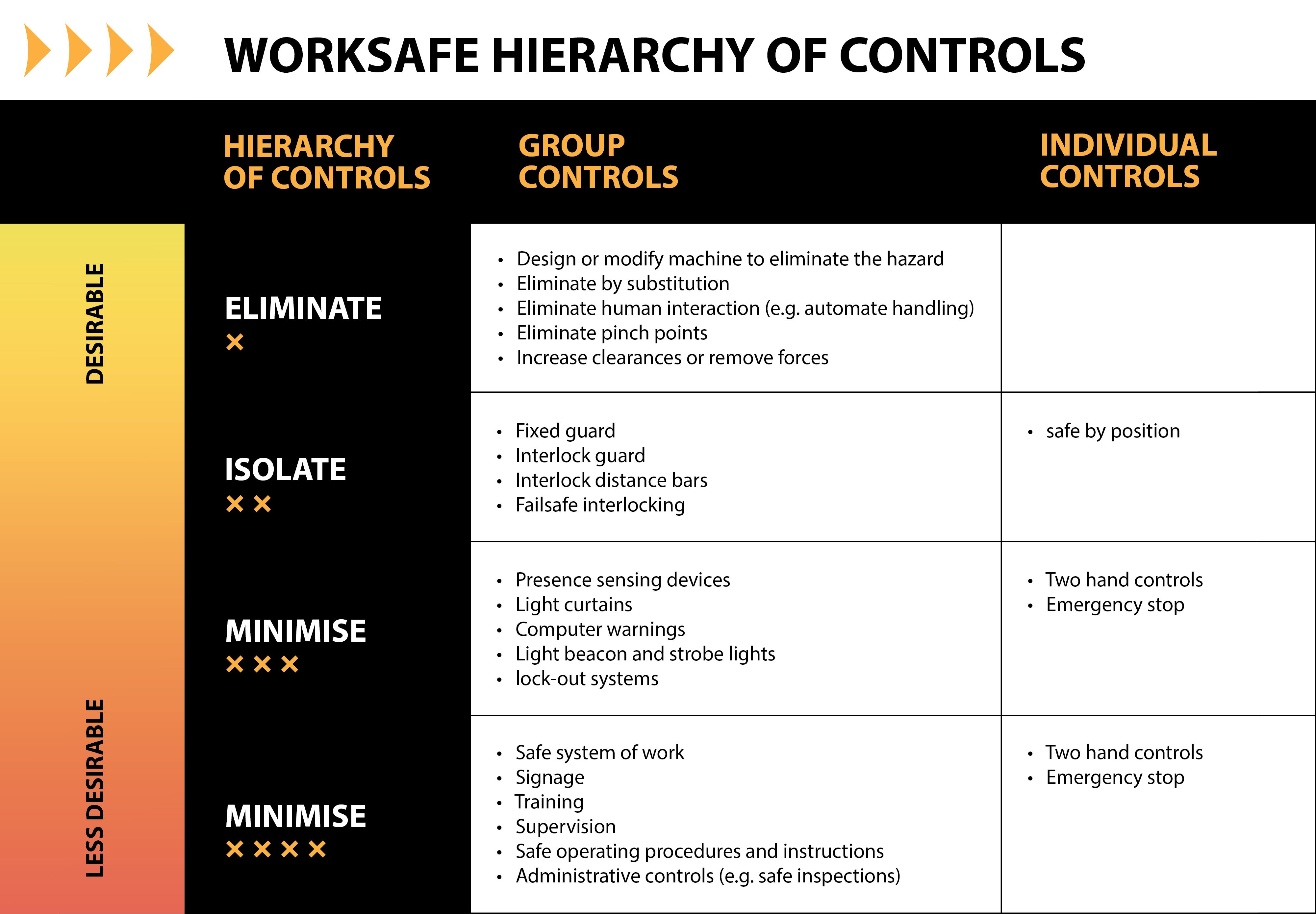

WorkSafe suggest a hierarchy of controls approach as suggested in the diagram below:

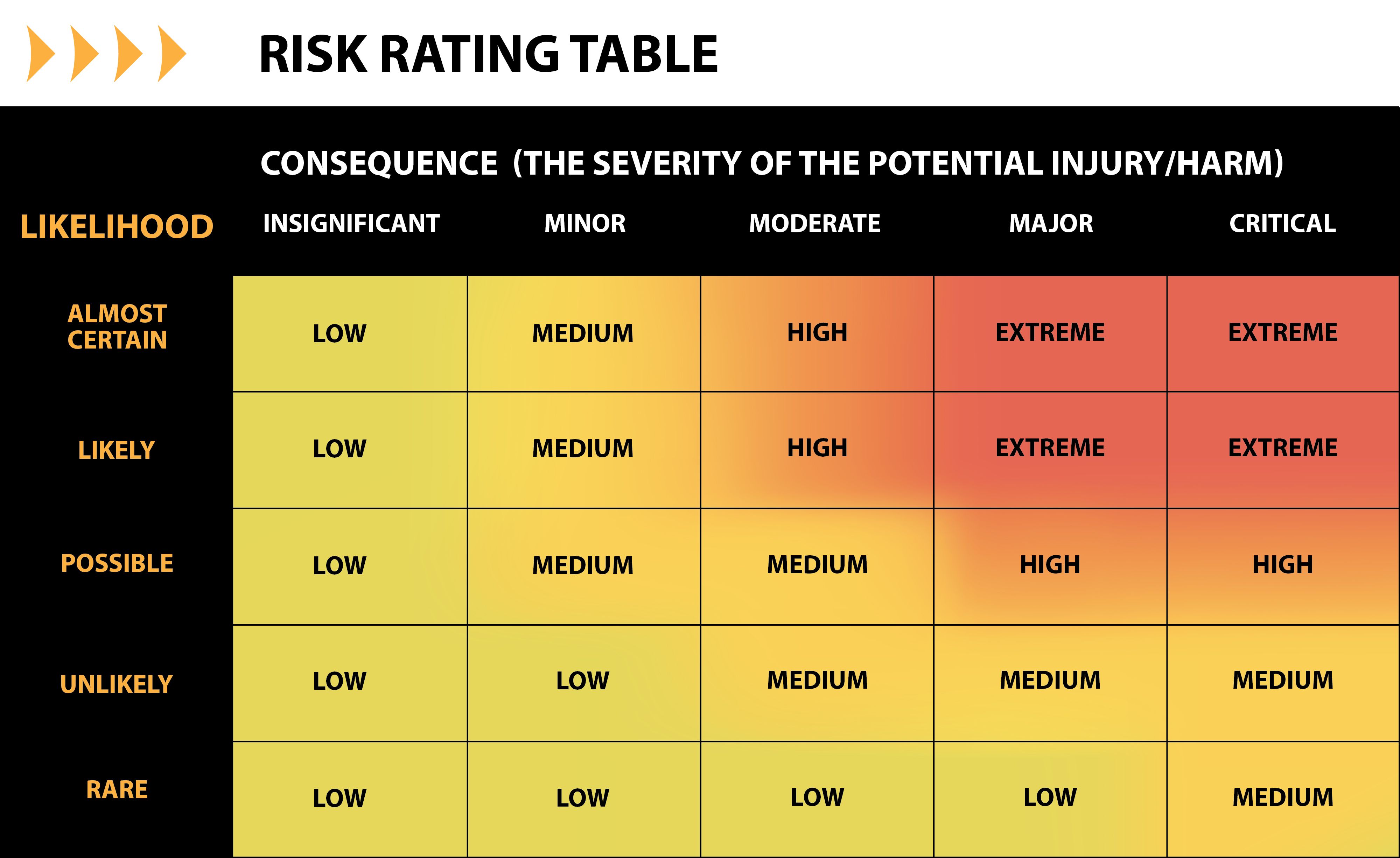

You can assess the risk by using a table such as the one here, or you can simply classify your risks as “high, medium, low” (whichever works best for you).

Procedures for accidents, incidents, emergencies, and disposal

Procedures for accidents, incidents, emergencies, and disposal

Accidents

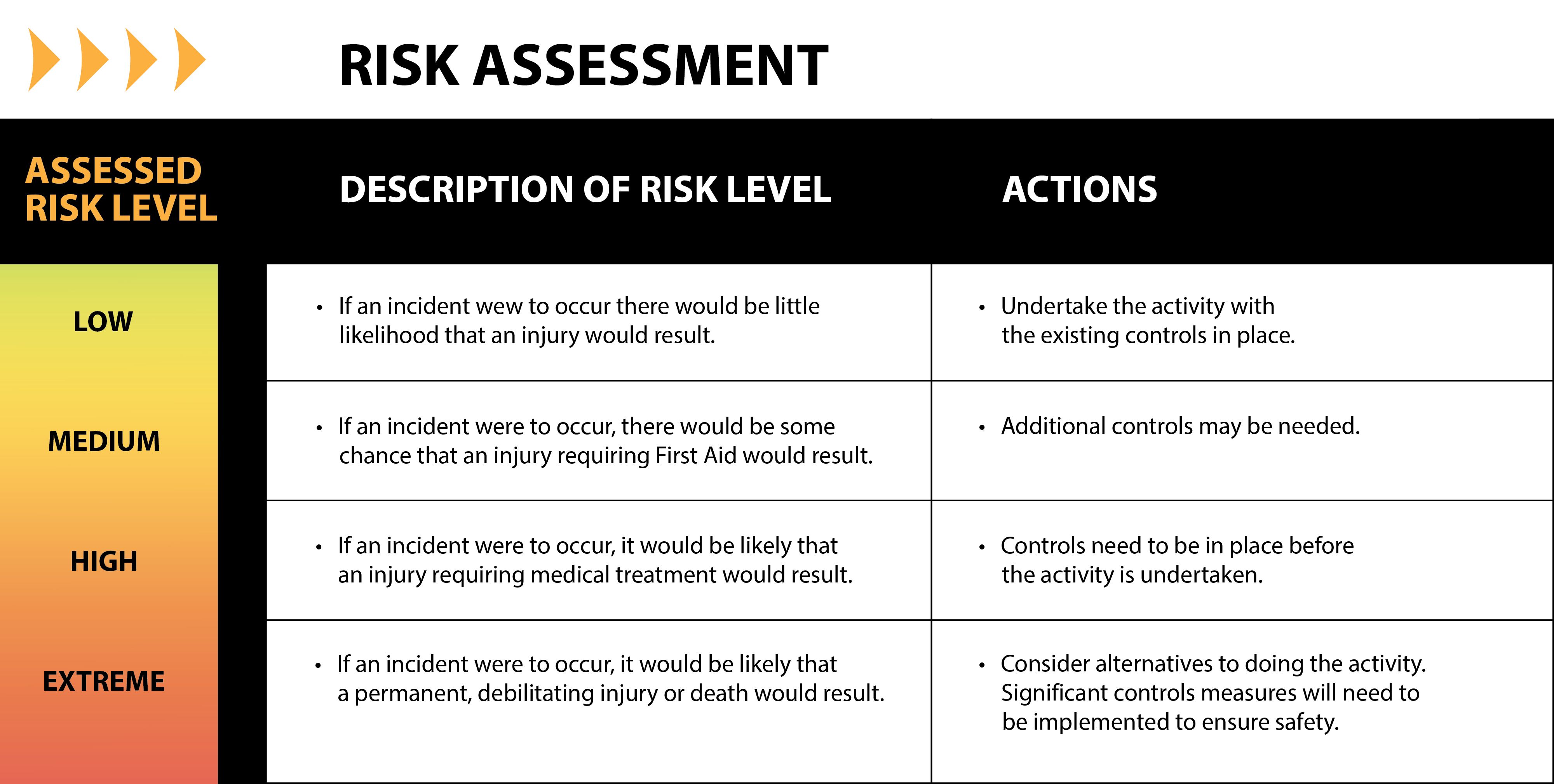

Let us look at a possible accident scenario and consider how it might fit in with chart below. In an area where staff are working, an item falls off the shelf and lands on the foot of a staff member.

How would you assess the risk, using the previous table or the table below?

If you think this is a low-level risk, or possibly “medium,” we would agree, but if you change the scenario so that an item falls on a member of the public instead of a staff member, you could argue the risk is now increased.

Members of the public include small children and the elderly, and if an object falls off the shelf and lands on either of those, they may end up requiring medical treatment. So now the risk is high, and you may need to put controls in place (e.g. a lip on the shelf).

In this example, your procedure would state that you have assessed the risk of objects falling off the shelf as “low” and that you can continue the activity with the existing controls in place.

BUT, if staff were regularly being struck by objects that fell off the shelf, you would review the procedure and install additional controls.

Incidents

An example of an incident could be a chemical spill or a flood or leaky roof that may lead to mould growing. Another example to consider is someone having a medical event on your premises. How would you deal with each of these examples?

The procedures that you write should have clear, short, simple steps, so that they are easy to follow. The person who will be following the written procedure might be stressed or panicked, especially if they are dealing with someone having a medical event.

Ideally the procedures should be readily available and in print that is easy to read.

Emergencies

Emergency procedures are usually associated with fire, floods, earthquakes, and power failure. Most organisations have procedures for dealing with these hopefully unlikely events.

Your procedures should have clear, short, simple steps, so that they are easy to follow. The person who will be following the written procedure might be stressed or panicked, especially if they are dealing with a flood or fire.

Ideally the procedures should be readily available and in print that is easy to read. If you can, make sure these emergency procedures can be accessed if you have to vacate your building. In the event of a fire or flood you will have to leave the building, so it is important that you have direct access to your procedures, as they may contain valuable information that you require.

Disposal

After assessing the potential hazards in your institution, you may decide that you wish to dispose of certain items, such as dangerous drugs, firearms, or items containing asbestos. You may wish to consider donating them to another institution or, depending on your collection policy, you may wish to consider becoming an institution with a special interest in dangerous drugs/firearms/asbestos, that will accept donations from other institutions.

If you do decide to dispose of chemicals, dangerous drugs, asbestos, radioactive material, or firearms and explosives, please contact the friendly collections team at Tūhura Otago Museum for advice or use the links to WorkSafe and ESR (radiation) below.

Documentation of staff training

Documentation of staff training

Training records should include the date and time the training took place, location, and who provided the training. Hopefully, you will all have had “induction training".

The training should be repeated every two years, not just to remind staff, but also to show that you have a system in place to ensure that staff are regularly trained.

The training document itself can be a simple questionnaire consisting of ten questions with “true or false” answers. It confirms that the training has been understood.

Review of the plan for effectiveness

Review of the plan for effectiveness

- Check to ensure that you have identified all the hazards

- Check to ensure that your standard operating procedures are robust and effective

- Check to ensure you have covered all eventualities

- Check that training has been delivered

- Document that you have reviewed the plan

There is a lot to get through when you do the first review because the management plan is new, but after that it revolves around keeping training up to date and documenting any incidents that have occurred, as well as how they have been dealt with using your plan. By documenting that your health and safety management plan is reviewed, you are showing that it is a “living” document that you refer to constantly, and that your organisation has a great H&S culture.